Author: Céline Claracq

California Dreaming? Now It’s A Reality For Contemporary Art

Has the West Coast become a top destination for contemporary art? It certainly looks that way. In Los Angeles, there’s The Broad, a new museum with an extraordinary contemporary art collection, and the sprawling art complex of Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel in the burgeoning downtown art district; Zurich’s Karma International, New York’s Maccarone, and Berlin and London’s Sprüth Magers have all arrived in LA too; in the Bay Area, the redesigned and expanded San Francisco Museum of Modern Art just reopened, Gagosian has set up shop next door, and Pace Gallery now has a space in Palo Alto. San Francisco also hosted two contemporary art fairs mid-January, the fourth edition of FOG Design + Art, with more top-tier galleries participating, and Untitled, San Francisco, the Miami-based fair’s West Coast venture, which has released an impressive list of collectors, curators, and art world professionals in attendance at its inaugural event.

Adding to the West Coast’s contemporary art credentials is something new in the realm of photography, and not surprisingly, it’s in San Francisco. The first edition of Photofairs | San Francisco will take place in Festival Pavilion at the Fort Mason Center, January 27-29, 2017.

Photofairs | San Francisco

Organizers say the aim is to position the fair as the West Coast’s leading event for both seasoned and new collectors of fine art photography and moving image. Alexander Montague-Sparey, formerly Director, Specialist Head of Photographs at Christie’s and now the fair’s artistic director, says, “The hand-picked works presented . . . celebrate fresh and relevant material at the regional and international level. At the first edition of Photofairs | San Francisco, I am excited to put that spotlight on the West Coast, alongside European and Asian artists never seen in the Bay area and who present especially interesting opportunities in the market at this time.”

Featuring 34 galleries from 14 countries and 25 cities worldwide, Photofairs | San Francisco will showcase cutting-edge photography and moving image in a carefully curated approach that emphasizes contemporary living artists. Besides the two sections presenting, respectively, 30 new and established galleries and four galleries participating in their first US-based art fair, there will be a third section showcasing emerging and mid-career artists who specialize in digital media along with a program of talks and curated exhibitions.

As a result of the city’s spirited embrace of the medium, many passionate collectors of photography are found in the Bay Area and other parts of California. The fair will of course seek to appeal to these collectors, but it is also aiming to educate and stimulate an interest in photography specifically among new and existing collectors of contemporary art in the wider Silicon Valley area.

Photofairs | Shanghai

Photofairs | San Francisco is the sister fair of Photofairs | Shanghai, whose successful third edition closed on Sept. 11, 2016. Billed as “the leading destination for collectable photography in Asia,” the fair presents work by exciting, emerging artists from China and the Asia Pacific region along with masterworks to appeal to Chinese collectors, both seasoned and new, who are becoming more comfortable buying multiples. With 50 galleries on hand, the Shanghai fair once again recorded higher sales. Attendance also increased, topping 27,000 visitors, a trend seen elsewhere – in 2016, Paris Photo tallied 62,000 visitors, up 8%, and Photo London, 35,000 in just its second edition – pointing to the growing popularity of fairs for viewing, selling and buying photography. True, after two years Paris Photo dropped its bid to establish an offshoot in Los Angeles, but Photo L.A. did just celebrate its 26th anniversary with a lineup of 80 galleries last weekend.

San Francisco

So, will Photofairs | San Francisco sustain these trends? Or follow the example of Paris Photo, which failed to take root in Los Angeles? San Francisco has a heritage of photography and has always celebrated the medium. It enjoys an international reputation for photography and is, along with New York, the country’s most important city for it. Those factors, plus not being undercut by a lack of local support, as Paris Photo was in LA, give Photofairs a much better shot at success

San Francisco boasts institutions with a strong commitment to photography like the de Young Museum, where over 80 years ago Group f/64, a circle of highly influential modernist photographers, including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, held its first exhibition; Pier 24 Photography, with its remarkable Pilara Foundation collection and temporary exhibitions; and a good number of other photography galleries, including the Fraenkel Gallery, considered one of the finest in the world.

Then, of course, there is the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, one of the first museums to recognize photography as an art form. It has more than 17,800 photographic works, dating from the advent of the medium in 1839 until today. The recent three-year renovation that doubled the museum’s size, making it the largest museum of modern and contemporary art in the US, also nearly tripled the space dedicated to photography, which now fills most of the third floor. Spread over 15,000 sq. feet, the Pritzker Center for Photography is the largest space dedicated to photography in any art museum in the United States.

The SFMOMA, which reopened last May, is now functioning as the prestigious hub of an expanding cultural milieu and art marketplace. A number of blue-chip galleries have gravitated to its neighborhood. Larry Gagosian has opened his first gallery in San Francisco, a 4,500-square-foot space around the corner from the museum, and dealer John Berggruen is leaving his former address after 45 years and opening a 10,000-sq.-foot, three-story gallery near Gagosian’s. “The two galleries establish a small but significant critical mass,” says Berggruen, hinting at their power to propel future growth in San Francisco’s contemporary art market. Meanwhile, Pace Gallery has followed the westward flow of contemporary art and created a new space in Palo Alto.

While the Silicon Valley crowd has not shown as much enthusiasm for collecting as the galleries would like, one of its venture capitalists is supporting artists in another way by backing the Minnesota Street Project, a complex of subsidized studio and gallery spaces.

And as mentioned earlier, San Francisco is hosting successful contemporary art fairs. Untitled, Art, launched in Miami in 2012, debuted an edition of Untitled in San Francisco mid-January. This curated fair featured 55 exhibitors from 10 countries and19 cities in North and South America, Europe, and the Middle East and attracted an impressive list of collectors, curators and art world professionals.

The roster at FOG Design + Art grew to 45 galleries this year and was even more international than in the past. This fourth edition, held from January 12 to 15, attracted 8,000 visitors, almost double the number at the inaugural event. Prominent newcomers included Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, Gagosian, Kurimanzutto, Paula Cooper Gallery and Lévy Gorvy. Dominique Lévy cited “the energy and the support of collectors from the region” last year and “the long-term commitment to modern and contemporary art in San Francisco” as reasons for their participation.

So, returning to that question at the start, “Has the West Coast become a top destination for contemporary art?” Based on just these highlights of the art scene in San Francisco and Los Angeles, the answer is an emphatic “yes.”

Finding the Sense of Art in Life After January 20th

John Berger, in 1960:

“It is our century, which is pre-eminently the century of men throughout the world claiming the right of equality, it is our own history that makes it inevitable that we can only make sense of art if we judge it by the criterion of whether or not it helps men to claim their social rights. It has nothing to do with the unchanging nature of art – if such a thing exists. It is the lives lived during the last fifty years that have now turned Michelangelo into a revolutionary artist. The hysteria with which many people today deny the present, inevitable social emphasis of art is simply due to the fact that they are denying their own time. They would like to live in a period when they’d be right.”

From the Introduction to Permanent Red (1960), republished in The Selected Essays of John Berger (2001).

Watch Ways of Seeing, the captivating four-part BBC series written and presented by John Berger that revolutionized our perceptions of art. The book of the same title based on these programs and published in 1972 is considered one of the most stimulating and influential books on art ever written.

Today, “denying” our own time has got harder. Here are some articles on how the art world is “seeing” Donald Trump’s arrival:

Prepping for the inauguration with art

Lessons of the election for art

Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was a small, experimental liberal arts college founded in 1933 in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina whose enormous influence on the arts continues up until today.

In keeping with utopian ideals of the progressive education movement, its founders regarded the study and practice of the arts as central to liberal arts education and art as a way of living and being in the world.

When prominent figures of European Modernism like Josef and Anni Albers joined the staff after fleeing to America, an interdisciplinary approach was instituted that gave equal importance to painting, weaving, sculpture, pottery, poetry, music, and dance in the curriculum. The craft principles of the Bauhaus and experimentation also became integral parts of the teaching approach. The presence of European artists and teachers like the Alberses and the de Koonings also created a cosmopolitan environment at the school, despite the rural location in the southern United States.

Learning through experience and doing, discussion and free inquiry, the sharing of ideas and values of different cultures – all were part of the educational philosophy at Black Mountain. New ways of teaching and learning were tried. Not least important, a high value was placed on individuality.

The faculty owned and administered the college, and students and faculty served on the many committees that ran it. The school functioned as a community, with everyone participating in its operation, including farm work, grounds maintenance, construction projects, and even kitchen duty.

Many prominent figures in the art world taught and studied at BMC. A partial list includes Anni and Josef Albers, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, Ruth Asawa, Robert Motherwell, Robert Creeley, Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, Ben Shahn, Franz Kline, Dorothea Rockburne, Gwendolyn and Jacob Knight Lawrence, Charles Olson, Vera B. Williams, Arthur Penn, M.C. Richards, and Francine du Plessix Gray.

Decreasing numbers of students and mounting debts forced the school to close in 1957, but during its brief history, Black Mountain College made a contribution far out of proportion to its size to the emergence of ideas and artists that have marked the history of art.

The Liberating Spirit of Robert Rauschenberg

“Art is an experience designed to allow every individual to be and find themselves.” – Robert Rauschenberg.

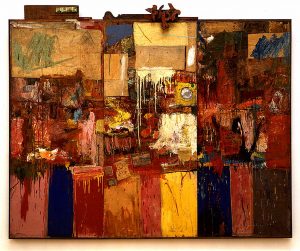

Leading up to the sweeping Rauschenberg retrospective that opened at Tate Modern on December 1 was another look back at the artist with a major exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing last summer. Rauschenberg in China centered on a single work, “The ¼ Mile or 2 Furlong Piece,” which had not been shown since 1999. Some 300 meters long (the distance between the artist’s home and his studio on Captiva Island, Florida), it consisted of 190 two- and three-dimensional pieces installed chronologically on walls that zigzagged through the UCCA’s Great Hall.

This series of works produced between 1981 and 1998, a “Combine” of sorts that dwarfs (at least in size) the groundbreaking Combines created early in his career, has been dubbed a “self-contained retrospective.” This display of the artist’s protean creativity of course includes pieces in which he worked “in that gap between art and life” he famously spoke of, incorporating objects from the real world in his paintings to produce jarring yet aesthetically compelling compositions. At the same time, the disparate elements of “The ¼ Mile” chronicle a reality of their own, the evolution of Rauschenberg’s ever-evolving and multifarious art.

The show at UCCA reveals another aspect of Rauschenberg’s urge to bring things together, too. He began “The ¼ Mile” the year before making his first trip to China. His experience during that trip, coupled with his belief that culture was a medium for uniting people and promoting understanding and peace, led to the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) project, a self-funded initiative in which he created and installed exhibitions of his work successively in ten countries (Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, USSR, Malaysia and Germany) between 1984 and 1991.

The ROCI China exhibition in Beijing, held in 1985, attracted some 300,000 visitors and had a profound impact on the development of modern art in China and the so-called ’85 New Wave art movement there.

The notion of “permission,” of his having a “liberating effect” on artists, is often mentioned in relation to Rauschenberg. There can be little doubt that what artists discovered in these exhibitions and Rauschenberg’s openness and interaction with them gave them “permission” not only to combine different media in their work, but also to follow their own creative impulses, while encouraging their fellow artists to do the same.

Rauschenberg and Black Mountain College.

Openness, interaction and mutual encouragement are things Rauschenberg himself found in a unique setting as he sought his direction as an artist. After studying briefly at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Académie Julien in Paris, he enrolled in 1948 at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina (see the “Looking Back” section).

A progressive school whose faculty included many of America’s foremost visual artists, composers, poets and designers, Black Mountain College was founded on an interdisciplinary approach to education that gave equal attention to painting, weaving, sculpture, pottery, poetry, music, and dance. Rauschenberg’s teacher there was the German-born artist and educator Josef Albers, who believed that learning called for direct interaction with life and familiarity with the physical properties of the material world. He also encouraged his students to work with a wide variety of materials.

Albers imposed strict discipline in the classroom, and Rauschenberg described Albers as influencing him to do “exactly the reverse” of what he was being taught. He may have chafed at Albers’ strict pedagogy, but his mentor’s emphasis on the importance of materiality in the creative process and of keeping art rooted in the real world seems bound to have resonated with Rauschenberg’s sensibility, intuition, and instincts.

And though lack of confidence is not something usually associated with Rauschenberg, it may have emboldened him to adopt the vocabulary that defined his work in the future – collages of images from magazines and newspapers, photographs, clothing, textiles, objects, cardboard, scrap metal – ordinary stuff of everyday life that he brought together in radically innovative ways from the 1950s onwards.

Rauschenberg’s longstanding friendship with composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham, both of whom taught at the school and shared his desire to integrate daily life into art, also goes back to the Black Mountain period. Rauschenberg has said that Cage had a “fantastic influence” on this thinking. “He gave me permission to go on thinking…he was the only one who gave me permission to continue my own thoughts.”

Those times spent in a remote corner of North Carolina, in a community of artists and an environment that fostered interaction, experimentation, and a spirited exchange of ideas, were critical to the future development of his art and of contemporary art in general. It was the kind of liberating experience – the “permission given” to follow their own ideas, wherever they might lead – that other artists have described in speaking about Rauschenberg’s influence on them in the following decades.

The current retrospective at Tate Modern, presenting works from his days at Black Mountain until his death in 2008, will run until 2 April. It will then travel to the Museum of Modern Art in New York (21 May–Sept. 17, 2017) and later to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

For more information, please visit:

A bigger stage for contemporary African art.

As noted in an earlier post, “flourishing,” “burgeoning,” and “booming” are words now commonly used to describe the contemporary African art market. Here we highlight some of the trends driving – and being driven by – this upsurge in interest and enthusiasm from the perspective of art fairs held since the summer.

Larger fairs with more visitors.

In just four years, 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair has more than tripled in size. The inaugural edition in 2013 presented 17 galleries in one wing of Somerset House in London; this autumn the fair took over the entire venue (including the courtyard for a site-specific sculpture) to accommodate the 40 participating galleries, 130 artists, and a record 17,000 visitors. Galleries from 25 countries have been featured at the fair so far. The upcoming 2017 Cape Town Art Fair (CTAF), slated for Feb. 17-19, has attracted the highest number of applications in the fair’s history. With more than 80 local and international exhibitors, up from 55 in 2016, this fifth edition promises to be bigger and much bolder in scope. For the “Tomorrows/Today” section, a key feature of the fair, CTAF’s new chief curator, Tumelo Mosaka, has chosen about ten emerging artists from Africa and its Diaspora for solo shows. The fair will also feature a new section in 2017 called “Unframed,” consisting of large sculptures and installations dispersed throughout the fair floor. This year FNB Joburg Art Fair featured 80 exhibitors from 17 countries. Attendance rose to 12,500, and sales totaled a record €2.8 million, compared with only €1.04 million four years ago.

New fairs.

New fairs are being organized both in and outside Africa in response to the excitement surrounding contemporary African art. Also Known As Africa (AKAA), the first art fair devoted to contemporary art and design from Africa to be held in Paris, hosted 29 galleries from 11 countries during the three and a half days, from Nov. 11 to 13. Its founder, Victoria Mann, had expressed hopes of welcoming between 5,000 and 8,000 visitors at the first edition in 2015, which was canceled because of the terrorist attacks in Paris. The fair this year sparked more enthusiasm than she expected: some 15,000 people attended. Art X Lagos (Nov. 4-6) featured a select group of galleries from ten countries in Africa and the Diaspora, presenting some 65 artists from Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Mali, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Egypt. ART X Lagos founder Tokini Peterside. ‘Our aim with Art X Lagos is to encourage greater patronage of artists across the board in Africa.” One way it did this was through the Collectors’ Series, a forum that engaged about 100 VIP art collectors on subjects such as collecting art as an asset. In a similar vein, artistic director Bisi Silva speaks of the development of “art ecosystem” both international and across the continent that would contribute to “the sustainability of artistic practice.” In Ghana, Art Accra hosted 25 galleries from Africa and elsewhere between Dec. 8 and 10. Boosting the new fair’s profile was a selection board made up of prominent figures in the world of contemporary African art: Oliver Enwonwu , Koyo Kouoh, Elikem Kuenyehia, and Ugochuwku Smooth Nzewi.

More galleries (some newly created) from more African countries.

At 1:54, out of the 40 galleries participating, 17 were doing so for the first time and 16 of the total were from the continent, including the newly created Gallery 1957 from Accra, Ghana. Cape Town Art Fair has more than 20 international galleries on the roster for 2017, but also many galleries that are the most representative of the African continent’s contemporary art scene, such as Addis Fine Art from Ethiopia, Afriart from Uganda, Art Twenty One from Nigeria, First Floor from Zimbabwe, and Galerie Cecile Fakhoury from Côte d’Ivoire in addition to the well-known South African players such as Stevenson, Goodman, MOMO, SMAC, Whatiftheworld, and Smith, among others. In another sign that the excitement around contemporary African art is gaining ground across the continent, FNB Joburg Art Fair chose to spotlight East Africa’s art scene in its Focus section, with Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan all represented. In Kenya, for example, where only a few galleries were found a short while ago, there is “a real blossoming of private galleries,” says Carol Lees, director of the One Off Contemporary Art Gallery in Nairobi. As for AKAA, founder Victoria Mann says, “one of the things that we’re proudest of is that half of the exhibitors come from Africa. So this isn’t just a fair with European and American galleries which show African artists.”

Next on the Paris calendar is Art Paris Art Fair (30 March-2 April), where the focus this year will be on Africa. Curator Marie-Ann Yemsi promises an “off the beaten path” approach, including a space devoted to video artists.

Also in Paris, there is talk of three exhibitions of contemporary African art being mounted at the Fondation Louis Vuitton next spring, including one presenting works from the collection of Jean Pigozzi, one of the largest in the world.

For more information, please visit:

Design on the Move

“We need to do something for design like what Tate Modern did for contemporary art in this country,” says Deyan Sudjic, director of London’s Design Museum. He recalls that before the Tate, contemporary art seemed “at the periphery of things,” or even “not relevant to the mainstream of British life.”

Now, with the opening of the Design Museum at its new home in the former Commonwealth Institute on 24 November, that “something for design” is in the making, and on the scale it deserves.

Formerly housed in a 1940s banana warehouse in Shad Thames, the Design Museum is moving to Kensington High Street, where it will join the Royal College of Art, V&A Museum, Natural History Museum, Science Museum, and Serpentine Galleries in London’s west end cultural district.

“Museums are special places,” says Sudjic. “The architecture of museums does matter a lot; it’s what makes people feel that they’ve come somewhere special.” And the new museum’s architecture is indeed special. One unique feature is the spectacular hyperbolic paraboloid roof that slopes inward. Architect John Pawson has preserved it as well as the building’s exceptional interior space in the £83-million conversion of this 1960s landmark. The roof will offer visitors a foretaste of the surprising and compelling displays of contemporary design they will find when they step inside. (The distinctive architecture did have one drawback: converting the building proved a bigger technical challenge than anticipated, resulting in a two-year delay in the museum’s opening.)

The Design Museum has almost 10,000 sq. meters of exhibition spaces, three times as much as at Shad Thames. This will allow it to install a permanent display of its collection for the first time and mount two temporary exhibitions.

A newly created, double-height lower level will accommodate galleries and an auditorium. On the ground floor will be the largest galleries, where temporary exhibitions will be staged, and the Design Museum shop and café. A learning center and reference library will be located on the first floor, and the museum’s permanent exhibits in the “Designer Maker User” display will be on the top floor along with the annual Designers in Residence program, a restaurant, and the members’ lounge.

London has long enjoyed a preeminent reputation in design. Its annual Design Festival, held since 2003 and featuring hundreds of events and exhibitions across the city; the prestigious PAD London fair; and Phillips’ design auctions at Berkeley Square, reinforcing its well-established presence in 20th and 21st century design, all support London’s claim to being the world’s design capital.

But Sudjic’s remarks point to another aim of the Design Museum. Besides merely reflecting London’s leading role in design, the hope is that in its new home, open year round to the public, it will attract many more visitors, perhaps an additional 400,000 annually. It will thus spark greater interest in and enthusiasm about design in a much broader audience and demonstrate design’s relevance to the “mainstream of British life” and to the lives of the many visitors from around the world who will add the museum to their list of sites in the city.

And what does the opening mean for Terence Conran, who founded the Design Museum in 1989? “All our dreams and ambitions to create the best and most important design museum in the world will become a step closer to reality.”

The two opening exhibitions:

– Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World (24 Nov. 2016 – 23 April 2017): installations of major new commissions by some of the most innovative practitioners in design and architecture explore a spectrum of issues that define our time, including: networked sexuality, sentient robots, slow fashion and settled nomads.

The exhibition asserts that design is deeply connected not just to commerce and culture but to urgent underlying issues – issues that inspire fear and love. This is a bold, multidisciplinary and global exhibition that aims to capture the mood of the present and establish the Design Museum as the home of design debate.

– “Beazley Designs of the Year” (24 Nov. 2016 – 19 Feb. 2017): Now in its ninth year, this event celebrates design that promotes or delivers change, enables access, extends design practice, or captures the spirit of the year. Nominees are presented in six categories: architecture, digital, fashion, graphics, product, and transport.

For more information:

Costume As Performance

Mark Coetzee, Executive Director and Chief Curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA), talks about the cultural significance of costume, why one collects costume, and why the Costume Institute is being created as part of the new museum in Cape Town.

Early humans might have employed skins and fur for warmth and protection, but for thousands of years clothing has not simply been used for protection from the elements. Civilizations have, through the ages, used clothing, jewelry, face and body painting, and body modification to express a myriad of different positions regarding morality, taboos, religious or class affiliations, wealth, national origins, aspirations, gender roles, and rebellion.

Understanding the history of costume allows us to comprehend the complex and deep history of humankind. We study costume to trace the similarities and differences of people, groups and nations. A costume institute acts as an archive of who we are, where we come from, and how our attitudes, morals, and values remain the same or change over time.

For too long, museums and the art world have differentiated between high art and the applied arts. Thankfully in the 21st century, we understand the extraordinary creativity and innovation that is happening in realms that would not have traditionally be seen as art. By collecting, preserving and exhibiting costume, museums use these artifacts as perfect examples and recorders of their time.

Museums, however, cannot only look to the past. They must also encourage us to confront the challenges and opportunities of the moment in time that we occupy. By helping us to understand the relevance and power of costume, we can make smarter, more educated, and more informed choices of how we want to use costume to express ourselves, how costume can liberate or suppress us, our impact on the environment through the fibres or materials we purchase, and our impact on workers and their human rights through which brands we support.

Costume began in Africa and then spread across the world as humanity migrated from its birthplace. Africa has extraordinary traditions of using costume to express our spiritual or religious traditions and affiliations, our allegiances to political parties, demonstrating our creative urges, making us seem more beautiful, enhancing our chances in finding a partner, identifying ourselves with certain cultural groups, expressing our positions on decadence or tradition, and our appropriation or rejection of aspects of costume from outside the continent.

The Costume Institute at Zeitz MOCAA takes as its mandate the responsibility to collect and preserve for future generations the extraordinary contemporary fashion arts to be found in Africa and its Diaspora and to use and exhibit the collection to educate and inspire. All costume designers originating from the continent, will be celebrated and exhibited. This institution has a mission to represent the diversity of creativity in Africa and its influence beyond our shores.

Africa has had huge influence globally. It is not a matter of comparing one designer with another, but rather understanding the cultural impact that costume design from Africa has had on the continent and beyond. The costume institute will also host exhibitions from around the world sharing them with local audiences. I hope that by being exposed to achievements from elsewhere, our designers will be better informed and challenged to push themselves further.

The Costume Institute Council, consisting of leaders in fashion, work to bring together funds for an endowment especially established to build the Costume Institute’s permanent collection. The Costume Institute is also the beneficiary of funds raised at the Annual Zeitz MOCAA Gala presented by Standard Bank Wealth and Investment. To guarantee the ongoing sustainability of the Costume Institute, the capital of the acquisition endowment is never touched, only the interest is used. This guarantees the Costume Institute will be able to fulfill its mission long into the future.

The Costume Institute is honoured to have received donations to its collections from various donors. These donations have come from the archives of designers themselves, from recent shows of young graduates, or from individuals who have seriously focused on building costume collections. An acquisition committee of leading practitioners, journalists and curators is in place that decides on all donations to ensure that only relevant, museum quality pieces, which demonstrate exceptional technical skill and cultural relevance, enter the permanent collection. Curators at Zeitz MOCAA also commission specific pieces by artists and designers for exhibitions and the permanent collection.

Museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London have been exhibiting costume for over a half a century. Their exhibitions are hugely supported by millions of visitors each year and have captured the imagination and aspirations of many generations.

With increasing attention being focused on the creative industries in Africa, the Costume Institute at Zeitz MOCAA will position costume designers in Africa along with their peers internationally and guarantee their contribution is not only acknowledged but also celebrated.

By providing space within a museum for collecting, preserving, researching and exhibiting costume, we demonstrate a concrete respect and value for the importance costume plays in our everyday lives and how the industry of fashion not only develops financial wealth but also the cultural wealth and power it provides to each of us to define ourselves on our terms, according to our choices, to those around us.

In 2017 the Costume Institute at Zeitz MOCAA will have a permanent home, with dedicated galleries, hosting changing exhibitions drawn from the permanent collection and selected loans. By creating a permanent site for contemporary fashion, we will develop audiences through an ongoing dialogue with lovers of costume through lectures, workshops, guided tours, social events, fashion shows, publications, and children’s educational programming.

The V&A Waterfront in Cape Town is the most visited site in Africa with 25 million visitors annually. We believe our location will guarantee us ongoing visitor numbers. The Costume Institute’s responsibility will be to ensure the quality of visit, to be sure our visitors leave better informed, enriched and inspired.

To determine if fashion is a form or art, we need, first of all, to define, or attempt to define, art itself. If we take the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of art as “a diverse range of human activities in creating visual, auditory or performing artifacts—artworks, expressing the author’s imaginative or technical skill, intended to be appreciated for their beauty or emotional power,” then it seems to me that fashion as it operates in the 21st Century is obviously art.

The lines between art, fashion, music, and digital media have completely blurred. Hierarchies no longer seem relevant in a time when we participate in every aspect of how we present ourselves to the world: how we dress, our social media pages, slang and street culture, selfies etc. We accept that we are being constantly monitored—photographed by others without our knowledge—on CCTV and other mechanisms, or knowingly by our colleagues, friends and family, or by ourselves through selfies. With the knowledge that there is no possibility to exist anonymously, but that we are constantly performing—like it or not—for the camera, we use fashion, hairstyles, and makeup as a way to tailor our image to the outside world, and we use our decorated bodies to project a message that we wish to propagate. I am convinced that fashion now functions as living sculpture. Using fashion we create visual aspects of ourselves, we bring attention to things we find beautiful, our bodies, the colours and textures of the fabrics we cover ourselves with, the silhouettes and shapes we change our bodies into. We are living artifacts, using the technical skill of designers, make-up brands, tattooing salons, sunbeds, etc., to express our imaginations.

Mark Coetzee, Executive Director and Chief Curator.

Interview of Laurent Le Bon, President of the Picasso Museum Paris.

© Musée national Picasso-Paris / Béatrice Hatala.

© Musée national Picasso-Paris / Béatrice Hatala.

Thank you, Laurent, for taking the time to speak with us today. You are one of the most innovative and stimulating people in the museum world in France. You began your career, as a curator at the Pompidou Center in Paris. You were then asked to take on the Pompidou-Metz museum project, and you became the director of that museum in 2010. Since June 2014, you have been President of the Picasso Museum in Paris. An art historian, author and professor, you have also curated major exhibitions. You are well acquainted with the challenges brought by changes in the museum world. We would like to ask you a few questions about this subject and hear your views.

In recent years, the so-called blockbuster exhibitions have been drawing record numbers of visitors. How do you explain their success? What does it mean? And who are the visitors?

The museum model is changing. Traditionally, museums were permanent, immutable places. Today our societies, our lifestyles, value the “temporary” more than the “permanent.” Or at least we are witnessing a blurring or erasing of this distinction. Telling “new stories” that are in step with our modern life and taking a fresh look at the major figures in art are what matters now.

With the globalization of trade and the increasing flows of information, major cultural events, which are promoted internationally with powerful marketing campaigns, attract many visitors from all over the world. The ephemeral nature of these events is part of their appeal. A blockbuster exhibition, like an opera or film, is a cultural “production” aimed at a public in search of exciting experiences.

“Packaging” the “permanent” as a temporary event is a strategy for renewing the museum offering and highlighting the collection. But it also offers the possibility of looking at works in new ways and revealing new aspects of them to an audience whose interest and curiosity must be continually aroused if they are to remain museum-goers.

The two major public cultural institutions inherited from the nineteenth century – museums and libraries – are at a crossroads today. They need to reinvent themselves and find new models. We knew that civilizations were mortal; now we are learning that museums are too. We frequently hear talk of museums being unchanging points of reference. More than ever before, the belief that museums are stable, permanent, and unvarying points of reference is wrong.

It is often said that culture is becoming more democratic. Is that really true? Are the record attendance figures for major exhibitions, which attract visitors from all over the world, proof of that? Or is the reality more complex? And what about the figures for the permanent collections of museums?

There is an overabundance of cultural offerings today, but generally a well-thought-out approach for promoting them and highlighting their value is lacking. However, in today’s very competitive cultural universe, developing a coherent and effective approach to attract diverse publics is crucial. Although more collections are being shown and the blockbuster exhibitions are a success, museums are attracting very few new people. So culture has not been democratized. When French people’s cultural habits are surveyed, the results are always the same: about 30 percent of French people go to a museum during a year, meaning that 70 percent do not. That’s a lot! Especially considering how abundant the offering is.

The figures for the number of visitors to an exhibition also need to be viewed with caution because they are not always different visitors. A significant portion are people who come and then come back again. There are very few first-time visitors to art institutions.

The success of the prestigious major exhibitions obscures a very disparate reality. We cannot really draw any general conclusions from it concerning an improvement in museum attendance. There are 1,200 museums in France, but about twenty of them attract a large majority of museum-goers. That means 1,000 museums in France have very few visitors.

Today, the gap between large and small museums is getting wider, and many museums are in decline.

One new trend we are observing is museums choosing to work with “star” architects. Do you think this is essential now? For a museum to be successful today, must it be housed in an extraordinary building designed by an internationally renowned architect?

Yes, that is a real trend. Art institutions are choosing to work with big names in architecture like Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Tadao Ando, and Renzo Piano. But let me give you an example showing that a museum’s success depends on a more complex alchemy and that an exceptional building, no matter how impressive, does not guarantee a successful museum project. Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao is a fabulous success from every standpoint. The presence of this museum has transformed an industrial city in decline into a major international cultural tourism destination. Less than ten years after Bilbao, Frank Gehry designed the Marta Herford Museum in Germany. This contemporary art museum, which opened in 2005, has not enjoyed the same fate as the one in Bilbao, even though it closely resembles it and displays the Gehry’s unmistakable signature style. This museum has remains fairly unknown and has not turned Herford into a tourist destination. The quality of the architecture, whether the project involves creating a new building or renovating an old one, is of course important, but it is only one factor in a museum’s success.

In your opinion, what ingredients make a museum successful?

There are many ingredients. A top-notch collection is essential, but that is not enough. Some museums that have very unique and remarkable collections, like the Musée des Tissus, the textile museum, in Lyon, are having very serious difficulties.

At a time when the cultural offering is growing, I think it is essential to position a museum in a unique way, and its uniqueness will stem from multiple things. A museum needs to forge a distinct identity for itself. Besides the quality of the container and the content, the building and the collections, its strength will come from its originality. Telling a story and having a communications strategy to support it are important. Having a unique space, a distinctive cultural project, and a competent staff are essential too. Innovative artistic leadership and original programming are necessary. The welcome must be friendly and helpful. In short, hospitality, a spirit of warmth and cordiality, must be offered.

To sum up: a unique place, a quality collection and a hospitable welcome are the backbone of a museum. Those are the ingredients that are indispensable to the success of an art institution. And I believe that today, in such a competitive market, the smaller the institution, the more important it is for the place to be unique. A very good example is, I think, the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar, which was renovated by Herzog & de Meuron.

And what about the financial “ingredient”? Particularly for public museums, with the budget cutbacks we often hear about? Must museums take an entrepreneurial approach? How can they increase their resources

French museums are not so poorly treated, even if there is a lot of talk in the press about their shrinking budgets. Be that as it may, museums must increase their own resources and understand that in a situation where there is an abundance of cultural offerings, they must go out and attract visitors and adapt to the new global market if they are to survive.

To develop new resources, it is of course essential to attract visitors. But it also requires raising funds which presupposes an entrepreneurial approach. It is also necessary to develop international partnerships and co-produce with other institutions. High-quality exhibitions that are put on can sometimes travel, too, and thus reach a larger audience.

What do you think of the new art institutions being created in France by private individuals, for example, the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Maja Hoffman’s project in Arles, and the François Pinault Foundation in the center of Paris, at the Bourse de Commerce? How do the roles of private and public institutions differ, in your opinion, and how are the differences important?

All these initiatives should be greeted with enthusiasm. For example, what is being said and written about the project in Arles and the art patron Maja Hoffman seems very interesting. To my mind, any new initiative is praiseworthy and should be supported.

You said that the boundaries between the permanent and the temporary are being erased. Under those circumstances, how can permanent collections be promoted?

A museum must be a “moviment.” I think this neologism coined by Francis Ponge when the Pompidou Center was being built defines today, more than ever, what a museum must be: that is, a “monument” in “movement.” It is with this spirit of “moviment” that the permanent collections of a museum, especially if the museum is dedicated to a single person, like the Picasso Museum in Paris, must be kept in “movement.” Monographic museums are the most fragile. To arouse and sustain visitors’ interest, it must continually reinvent itself. It must be in constant movement. After the first visit, when the excitement of discovery has passed, ways must be found to stimulate visitors’ curiosity and make them want to come back again. In the past, the fragility of a monographic museum could be seen at the Picasso Museum. Between 1986 and 2009, the number of visitors per year decreased by two-thirds, from one million to 300,000. The year it reopened, there were 800,000, or almost three times as many as in the year preceding its renovation. A monographic museum must continually invent new ways of showing its collection.

How are you making the Picasso Museum a “moviment”?

Since the museum reopened in October 2014, works have been presented on five levels. The presentation is less linear, and we have an original exhibition strategy enabling us to show different works. Our dynamic programming strategy is designed to present Picasso’s work – there are 5,000 works in our reserves! – from different angles in relation to different themes so as to offer new perspectives in the temporary exhibitions. The current exhibition, “Picasso and Sculpture,” is attracting 2,500 visitors a day. It will be followed next autumn by a Picasso–Giacometti exhibition. Then we will put on one focusing on Olga, Picasso’s first wife, who has always remained somewhat in the background. By revealing more about Olga, we will be able to see Picasso and his work in a new way. In 2017, in partnership with the Tate, it will be Picasso and the year 1932. We are seeking to illuminate a different period, which is neither the beginning, the end, nor the war years. The first Picasso retrospective was held in 1932, fifty-one years ago. It was also the year the first volume of the Zervos was published. You see, the idea is always to invent new stories and cast a fresh light on works.

Apart from the strategy of programming temporary exhibitions, we try to offer visitors a very pleasant welcome, one that is friendly and direct. To avoid having to wait in long lines, we have also instituted a system of 30-minute time slots so that visitors can avoid the wait if they wish. We are also developing cultural mediation activities. There are lots of new things to do in this area. For example, we have created a program in which children from a primary school have prepared the visit of the museum for a year with themselves as the guides for the residents of a retirement home. Some of these visitors are seeing Picasso for the first time, while others are rediscovering him through the eyes of a new generation, from a child’s perspective.

Everything that creates connections should be developed. The notion of “We” is motivating; we feel a need to share. We would also like to offer the possibility of spending the night at the Picasso Museum, as can be done in some other countries. It is fascinating and exciting to spend a night in a museum; one see the works and the place in a new way.

But it mustn’t be forgotten that the head of a museum that possesses a permanent collection also spends a lot of time conserving the works that are not being shown. And a lot of resources are used for conservation. That is the paradox of a museum. Nowadays, perhaps more than ever before, a large share of the artworks are not visible. There are more and more collections and collectors, but does that mean works are more and more “visible”? It’s not certain. I even think it’s the opposite. The public can see only a tiny portion of the very large private collections. Art is talked about more and more, we have the impression that the number of collections is growing, but, paradoxically, the works seem less and less visible.

Is there an art institution that you especially like as a visitor?

That would be the Insel Hombroich Museum in Düsseldorf. It’s an unusual place, with exhibition spaces lit only with natural light, no guards, and open on the natural surroundings. I have always felt attracted to museums where one has the feeling of sharing a story. The beauty and uniqueness of the place, the exceptional works, both inside and out, the osmosis with nature, and the hospitality you experience there are enchanting.

By Josette Sayers and Myriam Kryger.

Why All The Talk About Contemporary African Art?

Flourishing, burgeoning, booming… words heard whenever the topic is the market for contemporary African art. Rising auction results are of course one reason, but that’s not all. More African artists are getting solo shows, new fairs are being held, museums are expanding their collections and mounting exhibitions of African artists, and new museums featuring contemporary African art are on the way.

All these things are giving greater visibility to contemporary African art in Europe and the United States as well as Africa, where an effort is also under way to build a local market and ecosystem that will help sustain this momentum over the long term.

The Auction Scene.

Deciding that Bonhams should no longer have a virtual monopoly on this thriving market, Sotheby’s will launch its first modern and contemporary African art sales in May 2017. Hannah O’Leary, now head of the newly created Modern and Contemporary Africa Art department at Sotheby’s after ten years in a similar role at Bonhams, says the goal is to capitalize on the “enormous untapped potential” and establish “a significant profile in this field.” This move by Sotheby’s signals strong confidence that the market is far from peaking.

The overall results of Bonhams’ four modern and contemporary African art sales in 2016 did nothing to undermine that confidence. Its “Africa Now – Modern Africa” in London on May 25th, for example, brought in more than £2 million in total, double the previous year, and saw a host of new records at auction. The top ten lots, all works by Ben Enwonwu, El Anatsui, or Yusuf Grillo, sold for between £50,000 to £218,500, double or even triple their estimate.

The much higher, $1,000,000-plus prices occasionally paid for works by big names like El Anatsui, Julie Mehretu, and William Kentridge alongside those of other well-known contemporary artists are going to be seen more often, too.

Over the last four years, African art value has risen by 200%, with auction sales of modern and contemporary African art worldwide totaling $22.6 million. In 2016, sales of contemporary African art are up about 20%.

Numbers like these may be luring Phillips into the game, too – Arnold Lehman, former director of the Brooklyn Museum (a place known for its focus on contemporary African art), was in South Africa early this year scouting the terrain for them.

Smaller auction houses are tapping into this market. Piasa, a French auctioneer, will hold its third sale of contemporary African art, “Origins and Trajectories,” in Paris on November 17th, featuring works by 50 African artists and “highlighting the avant-gardism of African artists rather than the ‘otherness’ of African art.” Aspire Art Auctions, a new Johannesburg-based auctioneering firm specializing in historical, modern and contemporary art, will hold its first sale on October 31st of this year with works by both emerging and established artists. Founded in response to the rapidly growing art industry in South Africa, Aspire is planning to open a Cape Town office in November and hold its inaugural Cape Town auction in March 2017.

The Art Fair Scene.

There were some firsts on the art fair scene as well in 2016.

At the Armory Show, held in New York from March 3rd to 6th, “Focus: African Perspectives,” was devoted to “the artistic development and manifold narratives arising from African and African Diaspora artists.” It was the fair’s first invitational focus section to spotlight sub-Saharan Africa, with eight of the fourteen featured artists represented by galleries in Africa, including Cape Town’s Blank Projects, Whatiftheworld and SMAC, which were invited to participate with solo shows.

The fourth London edition of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair was held at Somerset House in early October, following the second New York fair in May. Showcasing more than 130 artists, both new and established, and 40 participating galleries (16 based in Africa), it was over three times the size of its inaugural edition. The larger representation helped to achieve one of the fair’s goals: to show there is no single “African aesthetic,” but rather a multiplicity of artistic visions and forms of expression, which is crucial to sustaining interest in contemporary African art. While fewer South African galleries made the trip to London, five from North Africa were represented, a relatively large number for an international event. Galleries from Ghana, Ethiopia, and Egypt were among the seventeen participating for the first time.

Coming up in Paris, which is seeking to rival London as a Mecca for contemporary African art, AKAA – Also Known As Africa – is the first art fair devoted to contemporary art and design from Africa to be organized in the French capital. Twenty-nine galleries representing some 115 artists have been invited to participate in this inaugural edition from Nov. 11th to 13th. Heavyweights like Galerie Vallois (Paris), October Gallery (London), ArtCo (Germany), and L’Atelier 21 will be there along with frequent international exhibitors Galerie 127 (Marrakech) and First Floor Harare (Zimbabwe).

AKAA founder and director Victoria Mann notes that the art scene in Africa has traditionally been understood according to prevailing Western narratives. But the origins of the art, she insists, do not necessarily define the link to Africa. AKAA views Africa as “fluid, with artists and designers who work in and outside of [its] borders . . . all contributing to this fluidity.” The notion of “fluidity” also applies to the interaction between the arts and design, a fertile symbiosis revealed in AKAA’s inclusion of African design at the fair.

In Africa, biennales like those in Casablanca, Marrakech, Dakar, Kampala, and Bamako are growing and gaining more recognition, and the list of art fairs is getting longer.

Held in early September, FNB Joburg Art Fair featured 90 exhibitions by galleries and organizations from 17 African and European countries as well as the United States. Though hardly a newcomer – this was the fair’s ninth edition – it did focus for the first time on East Africa, with works by leading artists from Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, Somalia, Sudan along with, of course, South Africa.

FNB Joburg made a big – and clearly successful – effort this year to raise its game to meet the challenge from the Cape Town Art Fair, whose goal is to become, with strong support from its European parent company and exhibitions specialist Fiero Milano, the premier event of it kind in South Africa and on the continent.

Speaking of Johannesburg, a new cultural district is under development in the city center. A revamped 80s office block in the Rosebank residential neighborhood will house restaurants, high-end design shops as well as the Cape Town-based galleries Smac and Whatiftheworld. More art spaces are planned for the Keyes Avenue area, too, where the Everard Read and Circa galleries are already located.

The Cape Town Art Fair is indeed positioning itself as a major international art fair that will “bring contemporary art from Africa to the world, and the world to Cape Town.” Held in a city that is home to Africa’s top galleries, it welcomed some 40 galleries and more than 130 artists last February. The CTAF is aiming to be even bigger and better in 2017, when it will coincide with the Zeitz MOCAA Gala preceding the autumn opening of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (see below). The fair is sure to help achieve Cape Town’s aim of becoming an – if not the – international hot spot for contemporary African art.

Elsewhere in Africa, the first edition of ART X Lagos will be held from Nov. 4th to 6th. It will feature selected galleries from Nigeria, other African countries (South Africa’s Goodman Gallery and Stevenson Gallery will be there, as will newly founded Gallery 1957 (see below) from Ghana), and the Diaspora, showing innovative contemporary art by over 45 established and emerging artists. Another newcomer is the Art Accra international art fair in Ghana, from Dec. 8th to 10th. It will present 25 galleries from Africa and around the world, with organizers touting Accra as “an excellent port of entry for the international art collector community interested in exploring the landscape of the art market in Africa.” So will collectors set sail for this new port? We will soon know.

Accra, by the way, is also home to a new gallery. Accra-based businessman and collector Marwan Zakhem opened Ghana’s first commercial art gallery in March. Gallery 1957 will specialize in cutting-edge contemporary African art. Explains Zakhem: “I wanted to create a commercial platform for artists based here to provide increased opportunities so they don’t feel they have to move abroad to pursue their careers.”

The question now is whether this new venture will enjoy the same success as, for example, the Johannesburg-based gallery MOMO. Founded in 2002 by Monna Mokoena, whose legal training could not compete with his love of art, MOMO promotes cutting-edge work by local and international artists and now has a new art space in Cape Town, too.

The Gallery Scene – Reflecting The Same Trend.

Major retrospectives and solo gallery shows in 2016 are both a reflection and driver of the flourishing contemporary African art market.

The list of solo gallery shows is long, far longer than when established South African galleries like Stevenson and Goodman were pioneering them locally and Jack Shainman was doing the same in New York. Of particular note are the exhibitions at leading galleries in New York and London, which point to the growing international stature of contemporary African artists. They include Nicholas Hlobo’s first New York solo show at Lehmann Maupin, the Burundian-born sculptor Serge Alain Nitegeka’s show at Marianne Boesky Gallery, Eddy Kamuanga Illunga’s first solo show in the UK at October Gallery, Julie Mehretu at Marianne Goodman New York, and Romuald Hazoumè at Gagosian Le Bourget (Paris). Along with these are solo shows at a dozen or so other London galleries specializing in contemporary African art such as Jack Bell and Tiwani Contemporary, which are hoping for visits from collectors in the city for Frieze and 1:54.

Among the major retrospectives were an exhibition of the Malian photographer Seydou Keita at the Grand Palais in Paris and the first major solo exhibition in the UK of Keita’s compatriot, photographer Malick Sidibé, which opened at Somerset House during the 1:54 African Art Fair in October and will run until Jan. 15th 2017.

The Museum Scene.

“When the Tate, the Smithsonian and other similar institutions start putting on exhibitions of contemporary African art, then one knows that something strange and wonderful has occurred, that real change is in the air,” says Giles Peppiate, director of modern and contemporary African art at Bonhams.

What could be more convincing proof of “change in the air” than the creation of a new museum dedicated to contemporary Africa art. Next year, the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, the world’s largest museum devoted to contemporary art from Africa, will open in Cape Town. Housed in the historic Grain Silo, a 57-m-tall icon on the city’s waterfront, Zeitz MOCAA will comprise over 9,500 sq. meters on nine floors, with 6,000 sq. m of exhibition space, making it one of the world’s leading contemporary art museums. This new not-for-profit institution will focus on collecting, preserving, researching, and exhibiting cutting-edge contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora. Says executive director and chief curator Mark Coetzee: “Zeitz MOCAA will constitute a re-imagining of a museum within an African context: celebrate Africa preserving its own cultural legacy, writing its own history and defining itself on its own terms.”

That winds up our brief review of the contemporary African art scene. Check back at MarketBeat for more news about the fast-moving world of contemporary art as an eventful 2016 draws to a close and a 2017 promising exciting new developments gets under way.

And in the meantime, go ahead and show off your own artistic talent by carving a pumpkin for Halloween (even if it’s not likely to get you a gallery show…).